Welcome Avatar!

FTX has filed for bankruptcy. BlockFi is rumored to be filing for bankruptcy imminently.

Voyager filed for bankruptcy, was supposed to be bought by FTX, but the deal was never consummated. So they’re also in bankruptcy.

And of course, Celsius is in bankruptcy.

Blood in the streets.

While bankruptcies are terrible for all stakeholders (investors, lenders, employees, and, particularly in the case of financial products & services, customers), they always provide major learning opportunities.

Stakeholders are forced to look at what went wrong and, if possible, what can be fixed going forward for a business to continue without being burdened by large debts.

But that’s not always possible. Sometimes, the value of liquidating all assets of a company can be greater than the value of that company continuing business (even if it had zero debt!). Bankruptcies are messy and the process can seem confusing.

Here are 5 concepts to boost your bankruptcy knowledge and get you ready for what’s to come.

1. Free Fall Bankruptcy

Typically, a company’s management team and lenders have a sense that the company is going to file for bankruptcy well in advance of the bankruptcy occurring. This is especially true in cases of large public companies that have a lot of eyes on them.

That’s because lenders have debt covenants in place, management teams want the company to make it, and both parties have a vested interest in protecting the value of the company in some form. Astute investors and lenders know how to tell if a company is in trouble.

This gives stakeholders time to negotiate and sometimes agree upon a plan to restructure the company’s debt obligations to reduce their loans and interest and allow them to survive (often in exchange for most/all of the equity).

Bankruptcies that are planned in advance are “pre-arranged” (key terms pre-negotiated) or “pre-packaged” (all negotiations/documentation complete and creditors have already voted in favor of plan of reorganization). These bankruptcies can greatly reduce legal cost, stress on the company’s operations, and time spent in bankruptcy.

But sometimes, companies don’t plan in advance. Some companies, like FTX, seemingly go bust overnight and are forced into an urgent bankruptcy filing. No real negotiations with stakeholders. This is known as a “free fall” bankruptcy.

Free fall bankruptcies are expensive, lengthy and highly unpredictable. Add in a massive list of creditors, multiple international entities, intercompany agreements, missing funds, hacks, and lost data, and you’ve got a recipe for a multi-year, messy process where the lawyers win and everybody else loses.

A pre-packaged bankruptcy is the fastest option. You might have 1-2 months of negotiations and then another 1-2 months in bankruptcy. A pre-arranged bankruptcy is slightly longer and could take 3-6 months from the start of negotiations. A free fall, on the other hand, is unlikely to be shorter than 6 months. It could take many years (Lehman Brothers took over 14 years).

Note that these are all estimates and not hard and fast rules. Bankruptcies can be messy and negotiations can fall apart, particularly in complicated situations.

It’s impossible to guess at the length of a bankruptcy in a complicated case like FTX. We’d be extremely surprised if it is completed anytime within the next 2 years.

2. Voidable Preferences and Fraudulent Conveyances

Transactions that occur prior to a bankruptcy filing can be unwound, meaning the assets come back to the bankruptcy estate. This is meant to prevent “unfair” payments that are made as a company is nearing bankruptcy outside of the appropriate order of repayment to creditors.

Voidable preferences are payments or transfers that occur 90-days before a filing. This “lookback” period increase to one year in the case of transfers to insiders. The basic premise is that you cannot make payments to one creditor at the expense of other creditors.

Fraudulent conveyance is when a company transfer property but doesn’t receive reasonable value for it and is insolvent at the time of the transaction (or as a result of it). The lookback period is two years.

Bankruptcy trustees can “clawback” (reverse) these transactions. There is some risk that crypto customers who withdraw crypto from an exchange or custodian within 90 days of the exchange or custodian’s bankruptcy filing may be sued to return those crypto assets as preferential transfers - the law is complex and affected customers should seek specialist legal advice.

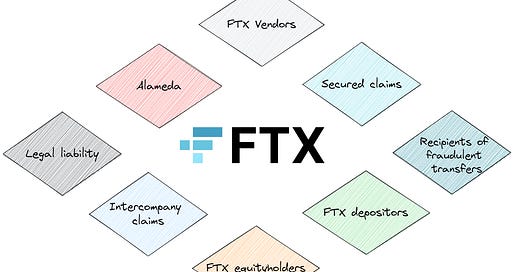

3. Competing Interests

Bankruptcies have many parties with different interests, priority of claims, and agendas. Different creditor groups are going to push for different outcomes in the bankruptcy because there is limited value available to be distributed and they want to maximize their “recovery” of their claims. It’s like bringing a pie to school and there isn’t nearly enough for the entire class. The difference is that instead of handing out slices to your best friends, you have to follow a hierarchy determined well in advance by the classroom’s rules. Last in line? Tough luck, Timmy.

Even within groups there are different types of creditors. For example, a hedge fund who bought user claims for 10 cents on the secondary market may have different goals than a user who deposited funds. The hedge fund might be happy settling for a 30 cent recovery because they tripled their investment, whereas users may not accept anything less than 80 cents because the money represents their savings.

4. Restructuring vs. Liquidation

Chapter 11 bankruptcy does not mean a company has to shutdown the business and disappear. In most cases a bankruptcy is a restructuring of the capital structure. The company and its creditors negotiate to reduce the company’s debt obligations and allow the company to continue operating with a new and improved capital structure. The previous equity almost always gets zero.

In a liquidation, the assets of a company are sold off and the business ceases to exist. Liquidations require a chapter 11 bankruptcy to be converted to a chapter 7. Asset sales can be done in a chapter 11 bankruptcy through a “Section 363” sale. The key difference is that a S.363 sale lets the company (known as the “debtor”), have far more control over the process whereas chapter 7 is handled by a trustee. A S.363 sale may also mean that the business largely lives on whereas a liquidation means there are no further operations.

Liquidations for larger companies are quite rare because they only make sense when value of assets > value of going concern even if there was zero debt. It means there is no willing buyer or creditor group who believes the present value of the company’s future cash flows is greater than selling it off for parts today.

FTX claims it has $9.6 billion in assets to cover $8.9 billion in liabilities. However, the valuation of much of these assets can’t be trusted because they are illiquid and marked to market. Just because the market cap or FDV of some token is in the billions does not mean that the value that can be realized (sold) is anywhere near that valuation.

5. Intercompany Claims, Subordination and Consolidation

This section is the most complicated but also one of the most important concepts for the FTX case. Creditors need to understand the entities that are included in a Chapter 11. FTX has included 134 entities. Big number. But is it everything?

Cash, hard assets, coins, and even intellectual property may have been transferred or sold below market value to related parties.

This image highlights the sheer complexity of the organizational structure and intercompany relationships for FTX. Multiple intercompany loans agreements, licensing and consulting agreements, asset purchases and more.

Equity holders are entitled to payment only after all creditor claims are fully paid.

The above example shows the existence of an intercompany claim, a secured loan from a third party at the HoldCo level, and an unsecured loan from a 3rd party at OpCo B.

OpCo B would have to first repay the entirety of its unsecured loan to the third party before there is any value leftover of its equity, which is owned by HoldCo. Similarly, OpCo A has an intercompany loan that would have to be repaid before there is value to equity holders. Depending on terms, this loan could rank “pari passu” (of equivalent priority) to something like user claims. Finally, the HoldCo has a secured loan with a third party that also needs to be repaid.

If everything were to be liquidated, the unsecured loan at OpCo B would need to be repaid using OpCo B’s assets, and the secured loan at HoldCo would need to be repaid with any value left before HoldCo equity received any proceeds.

Operating company claims being senior to holding company claims is known as structural subordination (HoldCo claims are subordinate due to the org structure).

Creditors of the HoldCo can push for substantive consolidation, which eliminates this disadvantage. All assets and all claims are viewed as consolidated, and intercompany claims are extinguished. This may end up being one of the critical factors in the FTX case.

Concluding Thoughts

If you understand these concepts you’re well equipped to understand all of the bankruptcies in crypto. There are more complexities, opportunities, and cautionary tales that will arise from these events. By the end of these bankruptcies (years from now) there will be a well known framework for managing crypto bankruptcies.

If you got value from this article, become a paid subscriber for DeFi Education for market commentary, deep dives, and more in-depth crypto analysis.

If you want to get up the curve on crypto from zero, we’ve put together a video course with over 40 lessons for those who are looking to launching a crypto career or want to learn how we analyze and research opportunities.

Until next time…

Disclaimer: None of this is to be deemed legal or financial advice of any kind. These are opinions from an anonymous group of cartoon animals with Wall Street and Software backgrounds.

We now have a full course on crypto that will get you up to speed (Click Here)

Security: Our official views on how to store Crypto correctly (Click Here)

Great value, thx! SBF, FTX, Alameda and all their “entities” and “inter company relationships” - I’d wager they knew what was coming. Financial crime here (opinion). Insane.

Thank you. Actually been reading the past year on bankruptcies and how they can benefit a company/individual. Interesting stuff