Welcome Avatar!

There have been longstanding requests for content covering basic finance concepts.

A lot of this information is easily found online so we will keep it quick and punchy and leave some links for you to dig deeper if you’re interested. If these posts are helpful please let us know in the comments and we will cover more general finance topics in the future. Note that we’ve covered some topics in depth already, including optionsand risk free rates.

Finance is an extremely broad term. When we say “we work in finance” we are referring to a “front office” role like investment banking, investing, trading, capital markets, etc. However, finance also includes things like accounting and banking. For the sake of our sanity, we will not be covering accounting in this post. Instead, we’ll focus on corporate finance / investing / valuation concepts.

Disclaimer: This information is best applied to traditional financial analysis - cryptoassets are far too new, volatile and reliant on grabbing investor attention.

Time Value of Money (“TVM”)

TVM is the concept that money today is worth more than money in the future because money today has earnings potential (can be invested for a return).

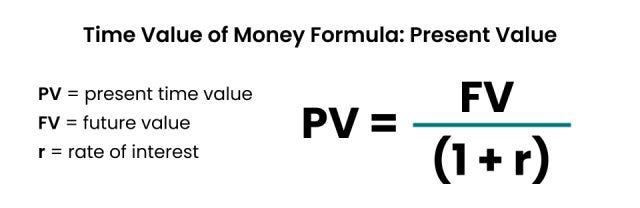

The present value of future money is a function of time, future money and the discount rate. The discount rate is the expected rate of return on an investment.

When you make an investment, you expect to make a positive return. The riskier you perceive the investment to be, the more you would expect to gain. The simplest way to understand this concept is from the perspective of a bank (zero). A bank makes you a loan and charges interest. The interest they charge is their expected rate of return on the loan. If you have bad credit or tons of other debt obligations, they will charge you a higher rate to try and account for the higher risk of not getting their investment + interest back in full.

The bank has to charge interest because money has an opportunity cost. Why would they give you a loan for no interest if there is someone else out there willing to pay them interest for the same capital? If there isn’t anyone wanting to take out a loan, they’d still be better off buying government treasuries for a 2.9% yield.

The formula above is the present value of money over one period.

E.g. the present value of receiving $100 in one year at a 10% discount rate is ~$91.

Time value of money underpins all investment decisions regardless of asset class. After all, as an astute capital allocator you only invest your money for an acceptable rate of return over a period of time.

Credit instruments like bonds and loans are much easier to value than equity because they have defined payments and capped upside (the most you can receive is your principal and interest plus fees). The payments are contractual obligations and you know how much you will get. That’s why credit instruments are referred to as “fixed income” securities.

A bond is an agreement between a corporate or government borrower and lender where the borrower gets money and promises to repay. The key components of a bond are the principal amount, maturity date and interest rate. Bonds and loans are similar but loans tend to come from banks which means they can cost more and come with more onerous terms and operating restrictions.

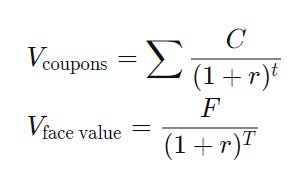

You can use the concept of time value of money to value a bond. The value of a bond is the sum of the present value of future cash flows plus the present value of the face value (the borrowed amount) of the bond at maturity. That’s a bit of a word salad, so here’s the equation (bond value is Vcoupons + Vface value):

You can read this article for more.

Capital Structure

Bonds and loans are credit and make up one part of a company’s “capital structure” or its sources of capital. The other main component is equity.

Note: there is a important distinction between balance sheet equity, intrinsic equity value and market equity value. From a valuation perspective, intrinsic equity value is a function of a company’s future cash flows. There is also market equity value which is shares outstanding * share price. Balance sheet equity is a company’s balance sheet assets minus its liabilities. The balance sheet equity is not particularly relevant for valuation purposes since valuation is based on future expectations. The market value of a company’s shares is implicitly assumed to account for a company’s future expectations.

As we mentioned in the beginning, time value of money underpins all investment decision making.

In the same way that a bond is valued based on the present value of future interest payments, companies are valued based on the present value of all future cash flows.

The owner of a bond (lender) is entitled to all the payments received on the bond. The owner of a company’s equity is entitled to the cash flows of the company. As a shareholder, you’re entitled to the future cash flows of the company, which determines the value of your shares today.

The present value of a company’s cash flows before debt payments is used to arrive at the “enterprise value” of a company. Note that enterprise value and market capitalization are not the same thing. Market cap refers to the value of publicly traded equity. Enterprise value is the total value of the company, of which equity represents one part.

Net debt refers to total debt minus cash.

Put another way, the value of equity is the value of the enterprise minus the value of debt plus the value of cash the company has. The image above depicts a healthy company.

If the value of the enterprise starts to decline as future business prospects dwindle and cash flows decline, the market value of equity can decline. Note that the market value of equity will erode first because equity is junior in the capital structure to debt. Companies have a contractual obligation to repay their debt - no such obligation exists in the case of equity. Equity is the last to get paid. As such, the expected rate of return for equity investing is higher than debt.

Debt obligations of companies can exceed their enterprise values, wiping out the equity entirely and even causing impairment of debt. That is why debt can sometimes trade significantly below “par” (the face value of the debt) - the market is pricing in the risk that the bonds will not be fully repaid and will instead receive a reduced amount or potentially nothing at all.

Discounted Cash Flow Analysis (“DCF”)

A DCF analysis values a business or asset based on the present value of expected future cash flows to be generated by that business or asset. The analysis accounts for the value of a company’s cash flows over a projection period (typically 5 – 10 years) plus a “terminal value” at the end of the projection period to account for the value of the business beyond the projection period (unlike bonds, the equity of a company doesn’t have a maturity date!)

Cash flows are discounted to the present value at a discount rate commensurate with the riskiness of the cash flows.

You take the sum of the present value of future expected cash flows

and add the Terminal Value to account for the value beyond the projection period.

DCF analysis is not used much in practice in public markets investing. It’s good to understand what it is and how it works conceptually and can even be useful to model out the value drivers for a company, but the output of your DCF is certainly not something to make an investment decision on. One of the best reads on common errors in DCFs is here.

One use of DCFs that is helpful is trying to reverse engineer market assumptions. You build out a DCF and back into the current price by adjusting assumptions on revenue, operating expenses, growth, etc. This way you get a feel for what kind of growth the market is “pricing in” and you can make a judgment call on whether or not you think the market is being aggressive, conservative or just right.

You can check out this guide for more info on the modeling side of things.

A DCF analysis is used to calculate enterprise value and equity value. With knowledge of the company’s capital structure, you can arrive at an enterprise value calculation, subtract the debt and add cash to get to equity value (there are other components but this is enough for a simple analysis).

You can compare your equity value calculation to the market equity value and determine, from an academic perspective, whether something is appropriately valued. This is the theoretical value of doing a DCF analysis.

Trading Multiples

Trading multiples take the market value of a company (either the enterprise value or equity value) and compare their ratios to another observable operating or financial metric (e.g. Revenue, EBITDA, # of users, etc.). Using multiples for valuation involves spreading these metrics for other publicly traded companies that have similar business and financial characteristics to the company you’re looking at. You then compare your target company’s multiples to the trading multiples of the peer group to see whether the market is valuing the company higher or lower. Note that being valued lower does not necessarily mean a company is undervalued - things are often cheap for a reason.

A common multiple is Enterprise Value to EBITDA - the value of the enterprise compared to earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization (essentially a proxy for cash flow). A better multiple, however, would be Enterprise Value to Free Cash Flow (an actual cash flow measure as opposed to a proxy).

The reason cash flow measures are superior to EBITDA is because there is far less financial wizardry companies can do when reporting cash flows - cash is cash.

Multiples implicitly account for all the concepts we’ve discussed in this post so far. A multiple reflects the market’s view of growth and risk. The market is paying $X for $Y of revenue / cash flow / users, etc. The higher X is in relation to Y, the more growth the market is expecting from the company.

A company with $1 billion Enterprise Value and $100 million in Free Cash Flow is trading at a 10x EV/FCF multiple. The inverse of this equation is FCF yield - you are investing in the company at a 10% annual FCF yield. A high FCF yield is good because a company can use these cash flows to invest in growth and/or pay dividends.

If we view multiples with the idea that a company’s Enterprise Value reflects the market’s view of future cash flows, you can see how all these concepts (time value of money, discount rate, DCF, trading multiples, etc.) are interconnected.

You can read more about trading multiples here.

That’s all for today’s post. In a future post for paid subscribers to DeFi Education we’ll go over some useful multiples to use in crypto.

This is a free post - if you found it valuable please give it a share!

If you’re reading this and haven’t subscribed yet, join our community below.

Disclaimer: None of this is to be deemed legal or financial advice of any kind. These are opinions from an anonymous group of cartoon animals with Wall Street and Software backgrounds.

Can't speak for the other non-finance readers, but this article was a level 4-5 for me.

Compared to the ol' VPN Usage one on BTB which was a level 2 for me (but perhaps truly a level 6 for less technical readers). Probably because I'm in software/tech.

I'd guess the readership can be split into 3 mains groups perhaps: tech/software, finance, and sales/marketing/ecomm.

Long winded way of voicing my appreciation for these finance 101 articles :)

Suggestion: maybe as a followup can you please apply these formulas+concepts on both a crypto token and stock, adjusting different factors to demonstrate how they change the underlying asset value?

Nice article fellas. One way I think about Time Value of Money:

Would you rather have $100 now? Or $105 a year from now? If you say, $100 now, what about $108 or $115 a year from now? At what number does your calculation change?

That's kind of how I think about opportunity cost and projected return rates. Can I do more with the $100 now vs. what the possible return would be in some asset.