Welcome Avatar!

Today we’re sharing some research requested from our last monthly Q&A (next one is on Saturday for paid subscribers).

In today’s post for our valued free subscribers we’ll be diving into a stablecoin that is launching this week. Aave’s GHO. On Thursday we’ll do a deep dive on Curve’s crvUSD for paid subscribers.

First, let’s briefly revisit stablecoin foundations and why they are important.

Taxonomy of Stables

Fiat backed stables are issued by a regulated company and backed with bank reserves and government bonds. Holders can have their funds blocked. Examples are Tether and USDC.

Cryptoasset backed stables are issued by a DeFi DAO to borrowers who deposit native cryptoassets like ETH. Smart contracts and oracles attempt to enforce a rule that assets are sold to repay debt if the collateral value falls below a safe margin, e.g. 130% of value of stablecoins. Examples include MakerDAO’s DAI and Liquity’s LUSD.

Hybrid stables can be backed by a combination of fiat stablecoins, cryptoasset backed stablecoins, and cryptoassets. FRAX is an example. Where a hybrid stable is backed by a cryptoasset created by the same issuer, this presents a particular risk (think UST/LUNA).

Who Uses Stables?

Broadly speaking, a holder of a stablecoin is either a lender or a borrower.

The borrower case is clear: someone deposits e.g. ETH in Aave or MakerDAO and borrows DAI. The lender case is less clear. Anyone holding a stablecoin has exchanged something of value for it. A stablecoin holder is indirectly lending this capital to the issuer, in the same way as a depositor is lending their money to a bank.

In the case of fiat backed stablecoins, the issuers invest the capital in debt instruments, pay their operating costs, and keep the remainder as profit. In the case of DAI, MakerDAO passes on the profit from investments, sharing 3.49% with DAI holders who elect to use the DAI savings account.

To achieve long term product-market fit at scale, a stablecoin needs to be cheap enough for users to borrow, but yield enough (or be useful enough) for crypto partcipants to keep on their balance sheets.

Utility is an important concept here. Tether is the market leader depite paying no yield to holders. We’d argue that the main reason for this is that /USDT is the most established and liquid trading pair. Swapping Coin A for Coin B usually requires an intermediate swap to USDT. When someone sells a cryptoasset, they usually receive USDT, and since this is also the currency they are most likely to use to buy their next cryptoasset, there is little incentive to swap for another type of stable.

Why Would Aave Launch a Stablecoin?

Aave and MakerDAO are established DeFi protocols which each have one core product. Aave facilitates peer to peer lending, and Maker issues an asset backed stablecoin. They have similar Total Value Locked metrics and operating costs, but differ substantially in net revenue.

MakerDAO has $5.7b TVL, annual revenues of $105.73mm and operating costs of $27.66mm. Maker makes a healthy profit and has a P/E ratio of 11.4x.

Aave has a similar TVL ($5.9b), larger FDV ($1.15b), similar fees ($114mm/year), but significantly lower revenue ($13.78mm). Adding back operating expenses (roughly 2/3rds of MakerDAO, $19.2mm) Aave isn’t profitable.

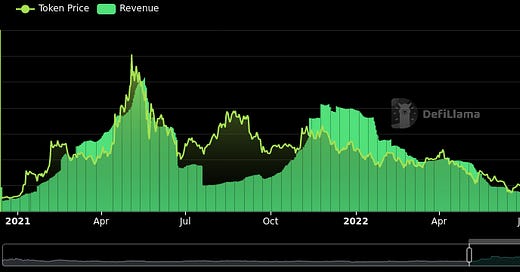

These charts illustrate how Aave (purple) vs Maker (green) revenues have evolved relative to their bull market peaks

MakerDAO isn’t doing that much worse two years into a bear market. Aave can’t cover its costs.

What’s the difference? Business model.

A stablecoin issuer is *creating* new money backed by assets. The same person who requests the loan provides the collateral assets.

A peer-to-peer lender requires different customers to supply each side of the market, and a double coincidence of wants to facilitate each transaction. In other words, Aave relies on both someone being willing to lend USDC and another customer needing to borrow it for a transaction to occur. Much of the TVL deposited isn’t used (utilization rate).

Peer to peer borrowing in crypto is driven by speculation / demand for leverage.

Rising interest rates aren’t conducive to speculative mania. Aave has no way to win as a peer to peer lender in the current phase of the economic cycle. A stablecoin issuer like MakerDAO can invest its reserves in treasuries and remain solidly profitable.

AAVE GHO (pronounced “Go!”)

Aave’s new stablecoin design is familiar. It’s a multi-collateral debt position similar to MakerDAO’s DAI. Its stability fee (borrow cost) is 1.5%, compared with 3.5% for MakerDAO. Unlike Aave’s peer lending system, 100% of this fee goes direct to Aave treasury.

Investors hope GHO will boost Aave’s token price and help to make the protocol profitable. We’re not so sure it will. Let’s dive in.

From first principles, anyone borrowing a niche stablecoin like GHO needs to swap it for a token they actually want. This could be a cryptoasset like ETH or a stablecoin which can be easily exchanged for fiat or other cryptoassets, like USDT. In order for GHO to be useful, it must either pay a yield or be swapped for another token. Nobody will pay 1.5% to borrow a token for no purpose.

This suggests that there need to be market makers willing to warehouse GHO on their balance sheets. But they’ll only do so if there’s a good enough reward. Tbills pay 5% on USD off-chain, and on-chain users can access a 3.5% yield via the much more Lindy DAI. Why would anyone want to hold GHO?

The success of the product in the short term is therefore based on incentives.

Without farming incentives (e.g. earn Aave for LPing GHO-USDT on DEX), we don’t expect high TVL for GHO. Why? There will be limited liquidity if market participants aren’t being paid to LP the asset.

Cheap borrowing is only part of the equation - a stablecoin also needs counterparties willing to swap a more valuable asset for non-yield-bearing GHO.

Key takeaway: bootstrapping GHO could be a serious challenge

How will Aave solve boostrapping? Options include allowing GHO to be staked in Aave’s safety module. This would give GHO a yield, stimulating demand for GHO.

Safety Module: Aave’s Safety Module (“SM”) sells up to 30% of staked AAVE to repay insolvent debt positions. If there is still a shortfall, new AAVE is minted (diluting AAVE holders) and sold on the market to raise further funds. The Safety Module pays yield to users who have committed to buy this newly minted AAVE as a ‘buyer of last resort’

Aave DAO also controls some liquidity incentives. A temperature check in governance proposes that liquidity incentives for Balancer AMM pools could come from:

Aave DAO

Reallocation of Protocol Fee Vote Incentive (PFVI)

Balancer Community Members

Aura Finance Community Members

Liquity

Others

GHO is modular: governance can delegate the ability to mint go to other entities known as facilitators. The first two facilitators are Aave v3 on Ethereum (deposit assets to mint GHO) and a Flashloan facility (mint unbacked GHO provided it is repaid in the same block). In the future, other permissioned facilitators could be added by governance, perhaps to mint GHO backed by Real World Assets. *If* GHO gets traction and good underwriters of RWA debt partner with Aave, this could lead to significant revenue, but it’s too early to evaluate this now.

GHO also competes with part of Aave’s core business. Assuming GHO succeeds and so trades at par with USDC, why would anyone pay 2.5% to borrow USDC on Aave when they could simply mint GHO for 1.5%? This will drop the utilization of USDC deposited on Aave and so lower the interest rate (incentive for borrowers to supply assets). Aave would earn more fees creating a GHO borrow rather than facilitating a USDC borrow, but at the cost of making Aave less useful for holders of other stablecoins.

Software Security

Interestingly, a portion of collateral appears to become locked in the system. For example, assume $100mm of GHO is issued. In a year, there will be $1.5mm of interest due (payable in GHO), but no additional GHO minted to cover the interest. Repayment of all the debts depends on Aave treasury recirculating GHO into the market. This has been commented on by two auditors, but the practical impact is uncertain and likely minimal.

We dug through the audits because smart contract security is important for a stablecoin. GHO has had 6 audits so far, and the latest (Sigma Prime, July 2023) isn’t encouraging. A High severity issue was found, very close to launch.

A audit flagged an issue where the code implementation didn’t match the spec in the technical paper. Attention to detail matters. And. As usual, we pay attention to code quality. There’s no inline comments, zero address checks are missing, the solidity version wasn’t fixed, there were typos, unused variables, inconsistent variable naming, minor issues around emitting events, etc.

Overall, the audits don’t give a high level of comfort about the caliber of the developers. The bug bounty is a weak $250k. And the GHO product itself is quite underwhelming.

Concluding Thoughts

Active traders: during the launch, GHO may go off peg due to light liquidity, and you could get paid to help bring prices back in line.

Don’t curve the Curve stablecoin, which we’ll be diving into for paid subscribers on Thursday.

Thanks for being a valued free subscriber to DeFi Education. To support the newsletter and receive ~2 additional posts per week + access to our monthly Q&As, join the paid community.

Disclaimer: None of this is to be deemed legal or financial advice of any kind. These are opinions from an anonymous group of cartoon animals with Wall Street and Software backgrounds.

We now have a full course on crypto that will get you up to speed (Click Here)

Security: Our official views on how to store Crypto correctly (Click Here)

Just looked at that audit report and I would agree, that’s a nasty high severity finding that should not have made it to the audited codebase. Does not cast a good light on the quality of their testing that it was not caught.

I find it surprising how something that has a "professional" branding to it (esp with that institutional aave that was going around during the bull) has such sloppy coding/audit issues