Welcome Avatar!

On August 17th, the crypto market lost approximately $120 billion of value in a single day, or ~11% of total market cap.

Although dips aren’t a surprise to our paid subscribers (we called for an end to the echo bubble back in March), such a dramatic fall in one day is unusual, even in crypto.

Why did this happen?

Today we examine the concept of liquidity as a means to explain how a relatively small amount of buying or selling can have a disproportionate effect on prices and overall market values.

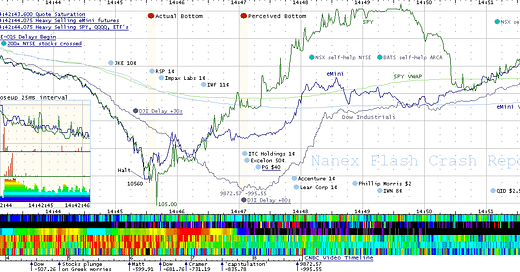

Liquidity is a dynamic which affects all markets. Even the US stock market has suffered from lack of liquidity, famously losing around $1 trillion (~9%) of its value in one day (the May 6, 2011 “Flash Crash”).

We’ll share some useful concepts and actionable advice to help you detect periods of low liquidity and manage the risk in your portfolio accordingly.

Case Study: The “Flash Crash”

On May 6, 2010 major U.S. equity indices plummeted in a matter of minutes, reaching prices 10% below the previous days close (and many stocks falling more than this). Then markets rebounded. Traders and regulators were initially puzzled, but as regulators and industry participants have access to timestamped trade data (just like a blockchain), it was possible to identify some root causes.

According to reports, a perfect storm of conditions combined to create the crash:

low liquidity / background weakness

withdrawal of market makers

the phenomenon of toxic flow

the impact of large derivatives orders

Low Liquidity

Liquidity means the ease with which an asset can be quickly bought or sold without causing a significant price change. There is a relationship between liquidity and volume: larger volume markets create more opportunities for market makers to profit by providing liquidity → this attracts competition → more liquidity is provided →volatility reduces as the market can absorb larger orders without the price changing.

Higher liquidity is good for investors as it reduces transaction costs and leads to greater price stability. This is obvious on a day when the whole crypto market is down - the less liquid “altcoins” suffer greater percentage declines than the higher liquidity “majors” (BTC and ETH).

Liquidity is also important as it determines the cost of buying or selling. If an investor wants to buy $100k of Bitcoin or Ether it can be done immediately with a cost of a couple of basis points. A $100k order in an altcoin may need to be split up into 5 separate orders of $20k, each of which will execute 1% away from the mid market price. In other words it costs $1k just to open your trade in the altcoin but just ~$175 to invest in Bitcoin. And the investor will pay transaction costs again to sell.

Liquidity includes orders posted to a limit order book (binding commitments to buy or sell if another trader accepts the price and the order has not been withdrawn), tokens deposited into an AMM liquidity “pool”, and also the potential for willing buyers or sellers to enter the market.

Simple example: there might only be bids to buy $5m worth of Ripple XRP token within 5% below the current trading price, but if the price dropped 5% instantly it may attract new buyers, especially speculators if the drop was thought to be due to an accidentally large sell order; or if the price of XRP is higher on other exchanges allowing for arbitrage. This liquidity wasn’t displayed on the exchange, but it still exists. Liquidity can be low if large or many participants exit the market or are unable to buy or sell - e.g. following the FTX insolvency.

On May 6, 2010 US stock markets experienced a drastic reduction in liquidity. Buy-side market depth (the quantity of bids for a security) plummeted to about 25% of its normal value. Cause and effect isn’t clear here - lack of liquidity means the price impact of any order increase, in other words the market will fall more in response to a given value of sell orders. The market falling can also contribute to lack of liquidity as participants de-risk, expecting further selling pressure.

Pockets of illiquidity can appear during weak markets when there is a temporary absence of willing and available buyers. In May 2010, the US markets had bounced from their March 2009 lows (following an 18 month bear market) but the economy was still poor. In August 2023, crypto majors had bounced from their November 2022 lows (following a 12 month bear market) but overall interest in crypto is still low.

The sudden evaporation of liquidity in both events exacerbated price volatility which created a feedback loop: as prices became more volatile → market participants became more hesitant to trade → further reducing liquidity → causing the orders of those who needed to trade (to reduce risk or limit losses in their portfolio) to have an even greater price impact →increasing price volatility.

Pockets of illiquidity can also appear in individual stocks or tokens, typically after a prolonged decline. Why? There are typically few remaining sellers after years of declining prices so markets can move up quickly on light trading. A large percentage increase in a single day lures in reactive investors who want to buy stocks or tokens which have recently performed well, but there is little supply available to satisfy demand.

Withdrawal of Market Makers

Market makers play a crucial role in providing liquidity to financial markets. They continuously stand willing to buy and sell an asset, ensuring that traders can always deal immediately. On May 6 market makers either curtailed their trading activities or withdrew entirely.

Several factors contributed to this withdrawal. Volatility made it challenging for market makers to judge the fair value of a stock and therefore set appropriate bid and ask prices. The presence of "toxic flow" made it riskier for market makers to maintain their usual quotes (spread and size). As a result, some market makers stopped quoting.

Toxic Flow

"Toxic flow" refers to order flow that provides an adverse selection for liquidity providers.

In simpler terms, those providing liquidity believe they are trading with participants who have superior information about either the true valuation of the asset, or order flow in the immediate future. Market makers lose to such informed traders, and they seek to limit their losses by widening their bid/offer spreads or reducing the value of shares they are willing to buy or sell. During a crash, flow becomes toxic to market makers as their inventory is worth less than they paid for it almost immediately, and a relative absence of willing buyers means they must pay to sell this inventory at a loss to reduce their risk. Often they sell to another market maker. This cycle causes programmed risk or P&L limits to be hit and the software (or human supervisor) dials back the firms’ level of participation in that product or asset class.

Price Impact From Large Derivatives Orders

One of the critical triggers identified for the Flash Crash was the automated execution of a large sell order in the E-Mini S&P 500 futures contracts.

A mutual fund (likely operated by Waddell & Reed) executed an order to sell $4.1b of E-Mini S&P 500 futures to hedge an equities position. Although this trader had entered similar size orders on other trading days, it usually elected to execute the order for 75,000 “E-Mini” contracts order over a 5 to 6 hour period to minimize price impact.

On May 6, the fund used a computer algorithm which aimed to participate in 9% of the trading volume without regard to price or time - an expensive lesson to be very careful in programming algorithms! Turning this algo on during a high volume (but low liquidity) trading period resulted in $1.9 billion of this order being executed aggressively in just 20 minutes.

Regulators believe this order helped trigger a temporary ~10% decline in the value of the US equities market, wiping off $1 trillion in value in a day.

Similarly, in the mid August crypto crash, liquidation orders (aggressive selling) amounting to only $800 million notional value contributed to a ~10% decline in the crypto market, wiping off $120 billion in value in a day.

More details on the dynamics around the Flash Crash can be found in the report produced by the SEC and the CFTC, the relevant regulators for the markets involved: the stock market and the equity index futures market respectively.

Note that this report, published 5 months after the crash when all the market data had been gathered in and analyzed, focused on a multi-billion dollar institutional order executed sloppily, and other market dynamics.

It did not implicate a retail trader placing relatively small algorithmic orders from his parents’ home in a suburb of London, England - as was later alleged in a Federal Grand Jury Indictment, headed at Para 34 “[Defendant] Sarao’s Manipulative Activity Contributed to the Flash Crash”.

Comparing Crypto and TradFi Markets

All of the dynamics explained above likely contributed to both the May 6, 2010 Flash Crash and the recent crypto crash in mid-August. But. There are key differences in the behavior of the more mature traditional markets compared with crypto markets during liquidity crises.

Crypto markets do not have any of these safeguards:

Volatility Pauses. TradFi markets can automatically pause when high volatility is detected, suspending trading but allowing participants to add liquidity to the order book.

Circuit Breakers. US equity indexes may not trade above or below price bands set at 7% and 13% from the previous closing price until a period of time has passed. Trading closes for the day if these markets trade 20% away from the prior close.

Rules for Automated Trading Systems. On regulated US exchanges, all execution algos must be supervised by a responsible human at all times. Rogue algos can be quickly shut down. Market participants must commit to extensive reliability testing and proper engineering of their algorithms before being allowed to connect and send orders to the exchange. Safeguards could include accounting for price, time, and total volume and other factors when executing an order to avoid disruptive price impacts. Firms who cause market disruption by running badly designed algorithms now face substantial fines from regulators and exchanges, and in extreme cases a possible ban from trading. Learnings from the Flash Crash led to changes in practices which make it extremely unlikely that a firm will execute a large order in such a disruptive manner again.

Crypto markets are decentralized and liquidity is fragmented between different venues. This means that it isn’t possible to enforce circuit breakers or rules to regulate automated trading systems. Some flash crashes may occur on only one venue due to extraneous factors (like the ability to deposit or withdraw a token being unavailable, leading to the supply or demand side running out of inventory).

Finally, certain products like perpetual swaps/futures are non-deliverable and non-transferable between venues, so there is theoretically no bound to how far they may deviate from the spot price in the very short term. Dislocations of up to 30% from fair value are relatively common.

Recent examples include YGG and other smallcap tokens (e.g. BLZ) which may have been manipulated by entities cornering the spot market and hedging their exposure in derivatives.

A key takeaway is that lessons from previous market disruptions, and the presence of regulators have forced traditional market participants to adapt in a way which reduces the odds of extreme crashes happening in the future. Crypto is either determined to ignore these learnings or is designed in a way (decentralization) where volatility mitigations can’t be applied. This means volatility, and the associated opportunities, are here to stay.

Opportunities

Filling Liquidations

A major difference between traditional markets and crypto is the real time publication of open interest and liquidation data by crypto exchanges.

In regulated markets, it isn’t possible to tell whether a counterparty is opening or closing a position. Real time open interest data allows you to view whether a series of recent trades represented a net increase or decrease in market risk. In crypto, you can also programmatically identify orders which are traders being forced to close their positions at a loss.

Why is this important?

It’s not possible to attribute whether a trader is informed or not when viewing an anonymous order executing on an exchange. This is the reason why large market making firms will pay a lot of money to know the source of an order. Firms will even set up exclusive arrangements to receive orders only from uninformed counterparties through their brokers. In TradFi this is called “payment for order flow” (PFOF) and is the reason retail apps like Robinhood can offer discounted or fee-free trading. The discount brokerage company is paid by the market makers to whom it sends customer order flow, rather than earning revenue from a commission paid by the customer. The customer still pays to trade as the market maker will quote a higher price for an investor to buy a stock and a lower price if the investor wants to sell. The difference is their revenue, also known as the spread. Market makers compete with each other and so more liquid instruments will have lower spreads.

In crypto, when forced liquidations occur, it is possible to know with certainty that these buy or sell orders aren’t entered by a trader with superior information about the fair value of the market or future order flow. And these orders are typically executed in a price-insensitive manner to avoid transferring the market risk of the position to the broker or exchange after the client’s account is depleted. Therefore providing liquidity selectively to traders who are being liquidated should be profitable, and therefore this is an aggressively competed trade for short term automated traders.

For slower moving investors trading manually a couple of times a year, a day where the crypto markets suffer a large decline (>5-8% for BTC / ETH) and lots of liquidations usually provides an excellent buying opportunity - either to capture a few percent of mean reversion with relatively low risk, or for adding to a long term portfolio at a better average price.

Investors can participate in crypto crash opportunities by:

buying out liquidated collateral at a discount on chain using DeFi

buying tokens on a DEX or CEX after a short period without any liquidations occurring following a large crash

setting orders below the market price and updating them daily (e.g. buy Bitcoin at $CurrentPrice * 0.9)

Stock indexes being more liquid and more efficient rarely provide such a “crash” opportunity - perhaps once or twice a decade, whereas crypto provides several opportunities per year.

Detecting Low Liquidity To Reduce Risk

Detecting low liquidity early enough can pay dividends if you act to reduce your portfolio risk before markets become volatile.

You can look at market depth (order book) on major exchanges to detect low liquidity. Liquidity varies with weekday or weekend, time of day, and recent volatility so you need to establish what you think is a reasonable baseline and then the threshold for liquidity being “low”.

Here’s a traditional “price ladder” style orderbook:

If you notice that the “buy” side of the order book has far fewer orders than typical for that time of day / day of week and the market is falling, and there are also larger than typical sell orders which keep moving down to at or near the current market price, this together with other supporting factors is an early warning of a market crash.

Another visual way to view this data is with an on-chart indicator:

Refer to the on-chart indicator captioned “Orderbook Suite” below the chart of Bitcoin covering the period of the August crash. Note that the orderbook imbalance had previously stayed within a constant range (marked by the thick yellow line). While prices were falling, but before the low liquidity / high velocity acceleration of the crash, note a significant increase in the imbalance between time 1 and time 2 (vertical yellow lines). This gave an early warning before price fell an additional 9%.

Another way to programmatically measure liquidity is to bucket a series of trades into groups according to a fixed volume transacted. Then relate the price change over the same period as a % to the percentage of orders where the aggressor was a buyer (seller).

Detecting low liquidity is useful if you want to try and avoid holding crypto during the worst performing days each year. We would encourage you to ingest API data from the major exchanges and model it yourself if you have the skillset. Otherwise off the shelf tools can provide snapshots as shown above. Investors can experiment with software and backtest rules which will automatically liquidate a part of their crypto portfolio when low liquidity occurs on a day when the market is negative, in the hope of avoiding most of the decline and being able to repurchase the portfolio at a better price.

In a nutshell, it is worth paying attention to liquidity levels to possibly warn of a potential crash (or large movement up) when:

majors are trading at an extreme for the month, or a multi month extreme

volume and price change on the day are higher than recent averages; and

there is a significant imbalance in the size of the posted bids/asks or in the buy vs sell volume (counting the aggressor side of the trade, the trader who pays to cross the spread, e.g. count a trade executed at the bid price as a “sell”) for more on this, read the papers on Volume-Synchronized Probability of Informed Trading (VPIN)

It is also important to be aware of the prior context: fundamental news and trader positioning. For example, the August crash started around $29k / BTC, near the highs for the year after months of hype about a crypto ETF being approved. Delays to the approval process or uncertainty about whether an approval would occur could cause an overreaction to the downside as investors who bought near the highest prices of the year panic on a dip. Recall that the market topped in 2021 after a (futures) ETF approval.

Crypto markets are often vulnerable to corrections after market participants are badly positioned from reacting late to good news. Another example is XRP making a high after a positive lawsuit outcome, only to lose nearly 50% of its value in the following months. “Sell the news” is a strategy for a reason.

Incorporating news and sentiment is more difficult to automate, but crypto markets are still so inefficient that a passive investor applying some simple rules can improve their return or reduce their cost basis by being aware of liquidity and market crash dynamics.

Summary

market crashes are more likely to occur in low liquidity markets - this can be due to major participants exiting (FTX/Alameda), general market or economic weakness, or forced selling from leveraged longs as the market declines after recent good news

low liquidity can be quantified by recording and modelling order book data - this is available for free from crypto exchange APIs

investors may be able to improve their returns by adopting a few simple trading rules, aiming to sell or hedge their portfolio if a crash looks likely; and employing a strategy of adding to their portfolio only after sharp market declines

DeFi users have special opportunities to buy tokens below the market price during crashes, as on-chain borrowers are force liquidated. We cover how to profit from DeFi liquidations in more detail for our paid subscribers.

Found this valuable? Support DeFi Education by becoming a paid subscriber and receive full access to all of our research!

Disclaimer: None of this is to be deemed legal or financial advice of any kind. These are opinions from an anonymous group of cartoon animals with Wall Street and Software backgrounds.

We now have a full course on crypto that will get you up to speed (Click Here)

Security: Our official views on how to store Crypto correctly (Click Here)

What a great and informative article!

I did not know that market makers pay Robinhood for access to retail investor orders. Ha, it’s like paying the pit boss for a chair at the table of bad poker players. Access to dumb money. I learned something today.